The case of the Warboys Witches is perhaps one of England’s most well known witch-trial cases. The details are related at length in the extensive albeit descriptively-titled 1593 pamphlet:

The most strange and admirable discovery of the three Witches of Warboys, arraigned, convicted and executed at the last Assizes at Huntingdon, for the bewitching of the five daughters of Robert Throckmorton Esquire and divers other persons, with sundry Devilish and grievous torments: And also for the bewitching to death of the Lady Cromwell, the like hath not been heard of in this age.

According to the account, when one of the daughters of Robert Throckmorton fell ill with strange fits, the family did not at first suspect witchcraft to be behind her illness. As his other daughters also started to share their sister’s strange symptoms however, suspicion slowly but surely grew, and the finger was pointed at local woman Alice Samuel, fuelled by the girls themselves naming her as their tormentor, along with, eventually, her husband John and daughter Agnes.

The Manor House at Warboys

(With kind permission of Philip Almond)

It was mid-March 1590 when Lady Susan Cromwell nee Weeks, entered the story. Second wife to Sir Henry Cromwell, (who was not only an influential man in the area but also happened to be the landlord of the Samuel family) Lady Cromwell and her daughter-in-law visited the beleaguered Throckmorton household to offer their sympathies for the suffering of the children.

According to the pamphlet, Lady Cromwell:

‘…had not long stayed in the house but the children which were there fell into their fits. And were so grievously tormented for the time that it pitied the good lady’s hear to see them, insomuch that she could not abstain from tears.’

It was not long before she sent for Alice Samuel; being unable to refuse a summons from the wife of the family landlord, Alice had no choice but to attend, whatever her misgivings might have been. Much to her horror, upon Alice’s arrival the condition of the ill children worsened, something that did not bode well for the Samuel family for:

‘Then the Lady Cromwell took Mother Samuel aside, and charted her deeply with this work, using also some hard speeches to her.’

Being thus accused of causing the suffering of the children, Alice was understandably upset, denying the accusation and retorting that the Throckmorton’s accused her unjustly. It wasn’t Master and Mistress Throckmorton who accused her, Lady Cromwell reminded Alice firmly, but the girls themselves who pointed the finger, the spirit that spoke through the girls when they were in their fits vowing that Alice was to blame for their pitiful condition.

Joan Throckmorton, hearing Alice’s denial, insisted that Alice was indeed responsible despite her protestations to the contrary, and that there was a spirit with her who was saying as much at that precise moment. The girl professed extreme surprise to learn that no one else present could hear the ‘spirit’ speak, as she herself could hear it loud and clear. Throughout this, Alice Samuel continued to insist that she had nothing to do with the strange illness that had invaded the household, but Lady Cromwell, unconvinced, wished to question her further in the presence of a visiting divine, Master Doctor Hall.

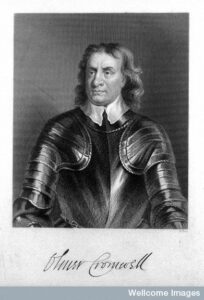

Oliver Cromwell, Step-Grandson to Lady Susan

(Wellcome Library, London)

Alice made excuse after excuse however, and it was clear that she intended to leave for her home without satisfying Lady Cromwell in her questions. Thus frustrated, Lady Cromwell pulled off the kerchief Alice wore over her head and cut off a lock of her hair. Not only that, but she took the old woman’s hair lace and gave both to the mother of the children with the instruction to put both in the fire to burn them in order to break Alice’s power over the girls. At this unexpected and unwarranted violation, Alice Samuel lost whatever composure she had remaining, uttering the fateful and – some later vowed, fatal – words:

‘Madam, why do you use me thus? I never did you any harm as yet.’

What happened next goes unrecorded, but Lady Cromwell left the Throckmorton household that night to return home. She did not sleep well at all, and was ‘very strangely tormented’ by dreams of Alice Samuel. Her agitated state woke her daughter-in-law who was sleeping with her, and she woke Lady Cromwell in turn, at which the older woman described how a cat, sent to her by Alice Samuel had tormented her in her sleep, threatening to pick the skin and flesh from her arms and body.

Lady Cromwell was so disturbed by the dream that she did not sleep again that night our of sheer terror. Not only that, we are told that ‘not long after’ she fell ill with a strange sickness. It might have been brushed off as coincidence, but the fits suffered by the lady were said to be similar in nature to those experienced by the Throckmorton girls. The only difference was that she was perfectly aware of the fact the whole time, unlike the girls who were periodically unaware of others in the room with them. Throughout, Lady Cromwell never forgot the words uttered to her by Alice Samuel, that she had not caused her any harm – as yet. Lady Cromwell passed away on 11th July, 1592, a year and a quarter after her ill-fated visit to Warboys.

It was downhill for the Samuel family from then on. In preparation, Agnes Samuel and Joan Throckmorton were lodged together in the Crown Inn in Huntingdon. Upwards of 500 people were estimated to have visited the pair, attempting and failing to bring Joan out of her fits. On the day of the assizes themselves in April 1593, John Samuel was finally compelled to utter words he had previously refused, admitting that he was a witch and had been party to the death of the Lady Cromwell and commanding Joan Throckmorton to come out of her fit. He was right to have been apprehensive about repeating the words, as the girl appeared as if cured the moment he uttered them. Alice Samuel had also been made to repeat the same words before this point and the same cure was witnessed.

That evening the judge himself along with several gentlemen and fellow justices attended the pair and it was proved beyond doubt that the only thing that ended Joan’s fits was a charge recited by Agnes.

‘As I am a witch and a worse witch than my mother, and did consent to the death of the Lady Cromwell, so I charge the Devil to let Mistress Joan Throckmorton come out of her fit at this present.’

Tragically for Agnes, the girl recovered in full view of those in attendance.

The following day three indictments were made against the Samuels: the first and most damning was that they were to blame for the death of Lady Cromwell through bewitchment, while the other two dealt with the bewitching of the Throckmorton girls and others in the Throckmorton household. All three were criminal offences under the 1563 Witchcraft Act, but bewitching to death carried with it the death penalty, a crime of which, after the matter was debated for five hours, the Samuel family were found guilty.

On the day of their execution, Alice Samuel was asked as she stood on the ladder in her final moments to confess again to the murder of Lady Cromwell through witchcraft. She was guilty, she told the assembled crowd, and, when asked why she had borne the lady so much animosity Alice admitted it was because Lady Cromwell had cut some of her hair and burned it along with her hair lace, and that her actions had been carried out in the spirit of revenge. She also implicated her husband in the murder, although right to the end she refused to involve her daughter, trying to protect Agnes to the end. (John Samuel himself never admitted to anything aside from the charge he was forced to recite and neither did Agnes, both going to the noose maintaining their innocence.)

Lady Cromwell’s widower, Sir Henry Cromwell, received the goods belonging to the Samuel family, as his right as their landlord. There cannot have been much due to their status, but there was enough money at least to commission an annual sermon to be preached at Huntingdon against the detestable sin of witchcraft. This was carried out until 1812; by that point however the focus had shifted to become instead an indictment and warning against the believing in, rather than the carrying out, of witchcraft.

Just driven past Warboys and wanted to learn more about the infamous witches. This was very helpful- thank you. The power of hysteria and delusion–what a sad story.

Hi Phil, thanks for your comment, I'm glad you found this post helpful! Yes, an incredibly tragic, and, unfortunately, not uncommon, occurrence during the period in question.

If you'd like to know more about the Warboys Witches there is a fantastic book on the case by Philip Almond, and I also have chapter on them in my book "English Witchcraft Trials".

All the best,

Willow

Wondering if my family have any connections to this story, as I was born a warboys and strange coincidence my birthday is 1st November all saints day