Often credited with being the last person convicted of Witchcraft in England, Jane Wenham fit the stereotypical image of a witch – old, living alone, with very little in the way of money or possessions. She had, by all accounts, lived in the village of Walkern for most of her life, but in 1712, events transpired to turn that existence upside down.

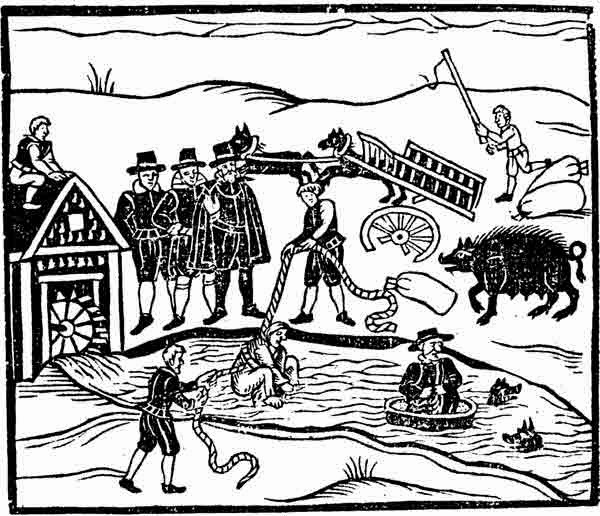

John Chapman, a local farmer, believed Wenham to have bewitched his cattle, causing the death of livestock to the tune of £200. Matters came to a head, however, after an incident where Wenham requested some straw from a labourer of Chapman’s; Chapman’s man refused and Wenham went away muttering (and, in some accounts took the straw anyway). Later that day, the labourer told his employer a most strange account – after the encounter with Wenham, he had felt compelled to remove his shirt and run very fast across the fields to gather straw from elsewhere, a journey that included running through a deep river. Chapman is documented as calling Wenham “A witch and a bitch,” and, after a good deal of abuse from the man, Wenham sought protection from the local magistrate, Sir Henry Chauncy.

Chauncy however was unwilling to arbitrate; instead the case was taken to the Reverend Gardiner, who, after listening to both sides, ordered Chapman to pay a shilling to Wenham for the matter to be dropped, advising them to live together in peace from now on. Clearly still aggrieved that he treatment had not been taken seriously, Wenham was heard to declare how she would find justice elsewhere before returning to her home.

As you would expect from such ominous mutterings, the case did not end there. A young maid in Gardiner’s household by the name of Anne Thorn began to act in the strangest manner. She suffered from terrible fits, falling down speechless and insensible. Once recovered, she told of feeling a similar compulsion to Chapman’s man, where she was forced to run through the fields to gather twigs. These were, according to Gardiner, his wife and a neighbour, Mr Bragge, found in her clothing and fastened with a pin. The bundle, viewed with all certainty as a witch’s charm, was quickly burnt in the hope of releasing the hold the witch had on the girl. As soon as this was done, Wenham herself appeared. Ostensibly to discuss some washing with Thorn’s mother, this coincidence was taken as a sure sign that not only was Wenham a witch, but that she had bewitched the maid out of spite towards Gardiner for his handling of her grievance.

The next morning, Wenham and Anne had a direct altercation; Anne stood by her assertion that Wenham was a witch, while Wenham scolded Anne for speaking against her, threatening, if Anne’s story is to be believed, dire consequences if she did not desist in such talk.

Over the next few days, Anne grew increasingly disturbed. The fits continued, increasing in intensity, and she made several attempts to drown or stab herself, all the while saying that Wenham compelled her to do so. In her delirium, the girl was said to be pointing at Wenham’s house, lamenting that she would never be well until she had collected more sticks. As things grew worse, accounts started of pins appearing in Anne’s hands, although where she found them was professed a mystery. The girl repeatedly threatened to harm herself and made to swallow these crooked pins, much to the horror of those around her. Wenham was brought to Anne on several occasions; the young girl scratched the woman in an attempt to break her hold, but to no avail.

It is clear, in hindsight, that disquiet had been building for some time. More people came forward to accuse Wenham. Thomas Adams said that Wenham had been caught stealing turnips from his field, citing hunger as an excuse. His best sheep then died, with three more following not long after. She was also accused of being responsible for the death of Richard Harvey’s wife and the death of two children in the village that fell ill and passed away not long after Wenham touched them.

As Anne’s condition worsened and the stories against Wenham mounted, she was eventually arrested and committed to Hertford Gaol where she would await trial. Wenham was searched for marks (evidence that she was in league with the devil), but none were found. On several occasions, the old woman was asked to say the Lord’s Prayer, and each time she was unable to do so, struggling at the line “Forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive them that trespass against us,” even when someone said each line before her. Chauncey’s son pricked her with a pin up to the head several times but failed to draw blood; only a watery liquid appeared instead, another sure sign of guilt. When her lodgings were searched, a potion was discovered, and, when Anne Thorn’s pillow was pulled apart, several cakes of feathers were found there, stuck together with an ointment said to be made from dead man’s flesh.

Wenham asked Chauncy if she could be swum, the traditional method of determining if someone was a witch, in order to clear her name. Chauncy refused, on the grounds that it was illegal and unjustifiable, the other tests to determine her guilt considered all the proof that was needed.

Wenham finally confessed to Reverend Strutt, Vicar of nearby Ardley, before Reverend Gardiner and a kinsman of hers by the name of Archer. She accused three other women of the village along with herself, but it seems this came to nothing as they were cleared without incident. Wenham confessed to making a contract with the Devil himself sixteen years ago, and said that although he followed her around, but she could give no more details. She was also certain that he could compel her to hang herself or drown herself at any given moment if he so wished. She was, she said, certain that a malicious and wicked mind had induced her to enter into this agreement.

Wenham was brought before Judge John Powell on 4th March, 1712. Powell, appears to have been sympathetic to the old woman’s plight, and is quoted as dismissing accusations of flying with the assertion that there was hardly a law against that. Despite Powell’s recommendations to the contrary, the jury found Wenham guilty of witchcraft, a verdict that meant death. Through the intervention of Powell, however, the death penalty was suspended, and it is said that Jane was granted a royal pardon from Queen Anne herself.

The case received great attention and a pamphlet war ensued, with at least nine written to condemn or exonerate Wenham during that time. Influential names rallied to the cause, and Jane finally lived out her days on the estate of William, First Earl Cowper, where she lived out her days until her death in 1729.

The case received great attention and a pamphlet war ensued, with at least nine written to condemn or exonerate Wenham during that time. Influential names rallied to the cause, and Jane finally lived out her days on the estate of William, First Earl Cowper, where she lived out her days until her death in 1729.