An interest in everything witchcraft related is a wonderful excuse to explore the vast and varied body of artwork with witchy undertones. A personal favourite is The Crystal Ball, by Pre-Raphaelite painter John William Waterhouse.

Finished in 1902, the painting depicts a young woman holding the ever-popular crystal ball. Shown with its sister painting, The Missal at the Royal Academy in the year of completion, by 1909 the pair was in the collection of Frederick Pyman, shipowner, and it is speculated that they may have been commissioned for his new home in Whitby. The Crystal Ball eventually came to rest in the dining room of Glenborrodale Castle in Scotland, where it remained until it was sold along with the castle in 1952/3.

Is the young woman a witch? A sorceress? She is clearly appealing to some form of magic, with a wand visible on a nearby book, which itself displays various signs and symbols. The background spied through the window is dark and menacing, and one cannot help but hope that the girl knows what she is getting into as she peers intently into the crystal ball in her hands. The most interesting feature however is the disappearing skull; disliked by the new owner it was painted over with a strategically placed curtain, and remained hidden until the amendment was discovered in 1994 when the painting came to Christies to be auctioned. Subsequently restored to its former state, the painting currently resides in a private collection.

Painting with the skull restored

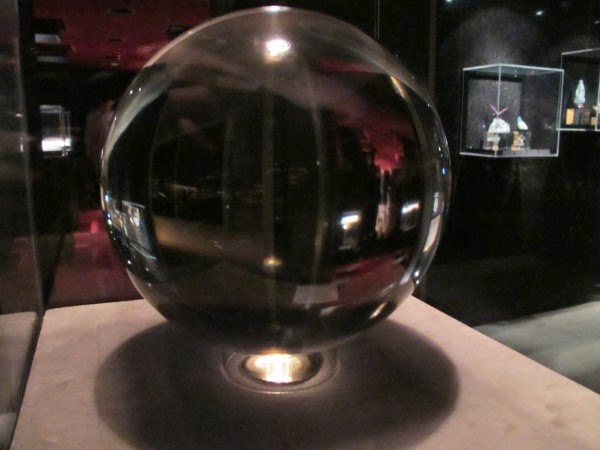

Crystal balls such as that depicted here have been used by numerous cultures throughout the centuries. Their main purpose is that of scrying, the practice of looking into a translucent surface with the intention of seeing images that can then be interpreted at the scryer’s discretion. Also know as “seeing” or “peeping”, the most common surfaces used are crystals, glass, mirrors, water, and even fire and smoke.

Although they can be traced back to at least 500AD in Europe, the crystal ball saw a resurgence in popularity in England in the mid 19thCentury, and the well-known image of a fortune-teller peering into a ball was largely a construct of this era. With access to more sophisticated apparatus, and a growing popularity among occultists and spiritualists, both demand and availability of crystal balls increased rapidly in the latter half of the century. In the early 1870s, for instance, an optician named Slater was producing balls at £1 11s 6d, but by late 1890s the price had dropped significantly, and in 1897 a Mr Vennan was selling them for the reduced price of between 2s 6d and 5s 6d. Writing in 1905 in his book Crystal Gazing, Northcote Whitridge Thomas points out that balls are kept in stock by the Society for Psychical Research, readily available should anyone require one.

The face of fortune telling itself was changing significantly over this period. Turning their backs on their more provincial roots, urban fortune tellers were taking on such titles as medium, character reader and clairvoyant, while the traditional “Mother” was replaced with the more sophisticated sounding “Madame”. Changes in the law played a part in this growing trend; the Vagrancy Act of 1824 and its subsequent amendments decreed it against the law for:

“Every person pretending or professing to tell fortunes, or using any subtle craft, means or device, by palmistry or otherwise, to deceive and impose on any of his Majesty’s subjects.”

This made it a wise career move for a savvy fortune teller to restyle his or herself, in order to avoid prosecution. Punishment under the act included hard labour or imprisonment. This clause was only repealed in 1989.

The balls themselves were used for two distinct purposes. Occultists utilised them as a method for spirit communications, making contact with those who had passed over or angelic entities. The other, more common use, is that already mentioned of scrying, during which images in answer to a question or a general picture of the future would be seen. The act of gazing into the ball acted as an aid to concentration, the ball providing a surface for the images to form on. The balls were taking over the role of more commonplace reflective objects or substances such as mirrors or tubs of water that had long been used by local cunning folk.

Belief in the efficacy of crystal balls was widespread, although not everyone was convinced of their ability to predict the future or reveal the identity of a thief. The aforementioned Northcote Whitridge Thomas, a British Government anthropologist renowned for field research in Nigeria and Sierra Leone in the early 20th Century, was rather matter of fact on the subject. Whilst denying the more spectacular claims for crystal balls, he explains at great length his certainty that people did indeed “see” with the aid of a ball, and cites many examples from his own experience with friends and acquaintances. He found that cultures across a wide range of countries and peoples had been crystal gazers, reasoning that if there was nothing in the process of scrying, they would hardly continue to do so for so many centuries.

Whatever one believes about their properties, there is no denying the beauty and fascination these balls hold. The crystal ball claimed to be the largest in the world currently resides at the offices of the American Ceramic Society, in Westerville, Ohio.

A sixty-five pounds flawless specimen is to be found at the Natural History Museum, Los Angeles.

The third largest crystal ball known to history is a sphere made of quartz crystal from Burma. weighing fifty-five pounds, it was made for the Empress Dowager Cixi (1835-1908) during the Qing Dynasty. Stolen from the Penn Museum at the University of Pennsylvania in 1988, the ball was recovered unharmed three years later.

Where is the black and white photo from? Year? Photographer? From an archive or a book or other?